The Number of Nukes Is Still Too Damn High

It is, seriously. Let me illustrate.

With Putin’s suspension of the New START agreement, there is now little more than goodwill to keep the biggest nuclear powers from increasing their arsenals. When weapons of mass destruction are involved, this is anything but reassuring.

After the mad nuclear arms race of the Cold War era, we thought we basically had the whole nuclear armageddon issue under control (or at the very least we’ve stopped really worrying about it).

But despite impressive disarmament efforts, which have decreased global arsenals from a peak of over 70000 warheads in 1986, there are still far too many nukes in the world. The number of weapons we are pointing at each other — and those we keep in storage “for later” — is mind-boggling.

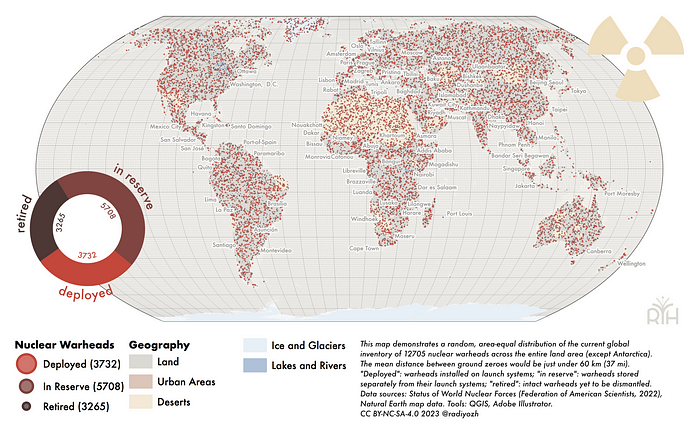

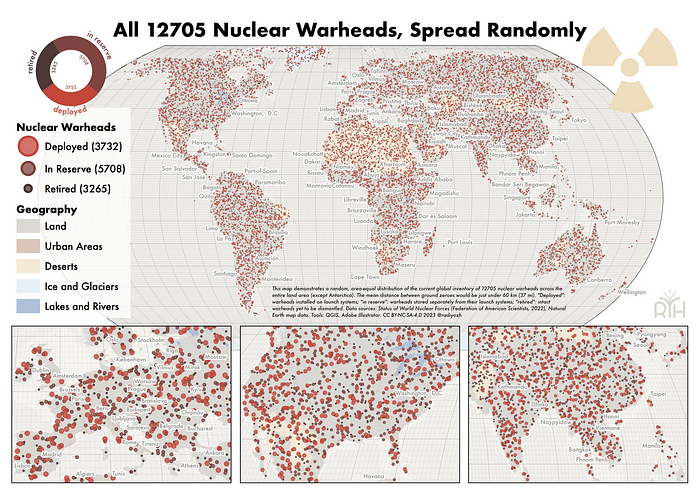

All in all, there are 12705 intact warheads in the world right now. This is an estimate from the Federation of American Scientists, the most authoritative source on the topic. I don’t want to get into discussions of what country owns how many missiles or bombs — weapons of mass destruction pose an inherent risk to humanity, regardless of who owns them.

If a nuclear conflict were to break out — something that could happen by accident, miscalculation, suicidal tendencies, fanatic nationalism, misguided utilitarian calculation, or a combination of those — the consequences for people all over the planet would be devastating.

I can’t comment on the different models estimating the impacts of even limited nuclear exchanges on the climate, food production, health care, communication systems, international transport, and especially on people, but I can try and visualize just how many warheads we are talking about.

Spreading The Nukes

To illustrate the global nuclear inventory, we distribute them equally across the entire land area (excluding Antarctica), about 117 million square kilometers.

We could drop one nuclear warhead for each 9234 square kilometers on Earth — the area of a circle with a radius of about 54 kilometers.

This is still fairly abstract, so for clarification I took the liberty of drawing an exemplary distribution of nuclear warheads on a world map.

Each dot corresponds to one of the 12705 active nuclear warheads.

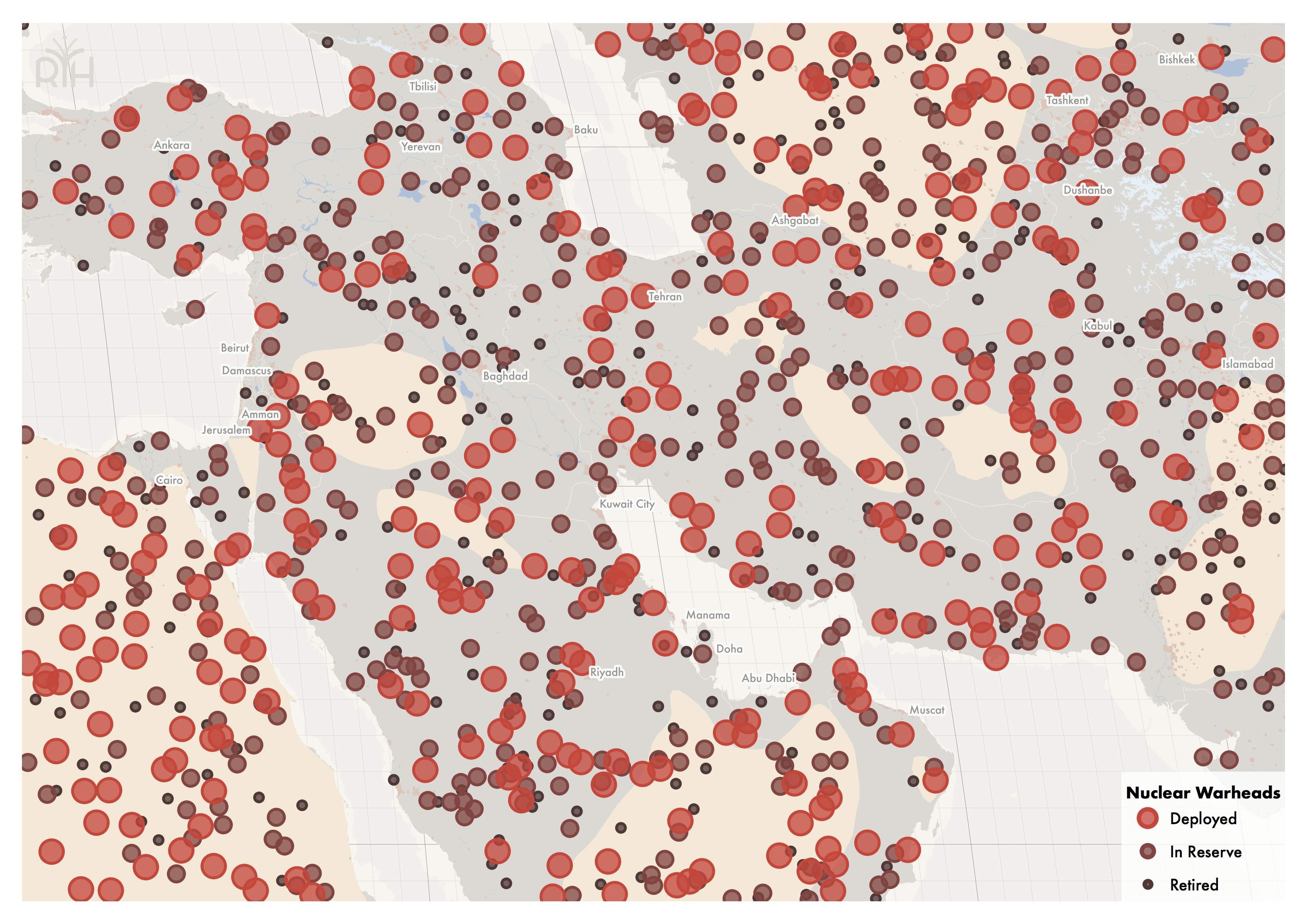

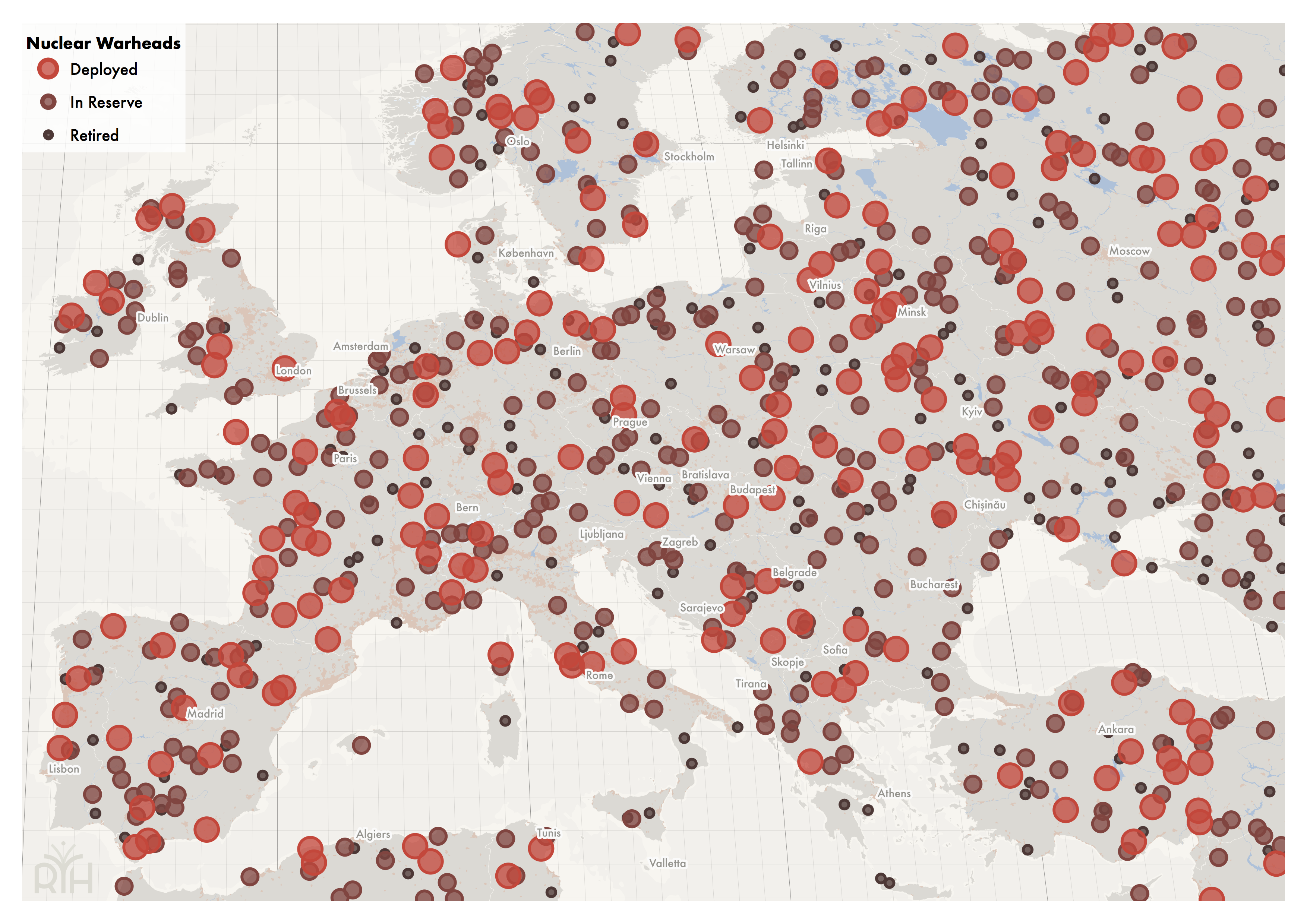

The large, bright red circles (with an outer diameter of 100 km) are deployed warheads, i.e., those that are at the moment coupled to their launch system (bombers, ICBMs, submarine-launched missiles, etc). These 3732 warheads are usually ready to launch at short notice, among them also a few tactical (non-strategic) nuclear weapons. The New START treaty limited the number of deployed warheads to 1550 for each party (i.e., the United States and Russia).

Warheads in reserve are displayed as medium, darker red circles with an outer diameter of 75 km. These are active warheads that are stored separately from their launch system, and thus take more time to assemble and launch. Nearly half of all warheads in the world are in this state at any given moment.

The smallest (diameter on the map: 50 km), darkest dots correspond to retired warheads. These are designated to be dismantled, but are still fully intact and could conceivably be coupled to a launch system. Until they actually are dismantled, they also constitute a serious risk and are therefore included in official statistics and also this visualization.

The ground zeroes are disturbingly close. A nearest-neighbor analysis reveals that the mean distance is just under 60 km, which is reasonably close to the density calculation further above. In other words, wherever you are, there is a good chance that a nuclear warhead could land 60 km or less from you.

Here are some regional close-ups.

As to potential casualties one can only speculate. This visualization assumes an area-equal distribution across all continents and islands (except Antarctica), meaning this includes the vast Sahara desert, Greenland’s glaciers, the Tibetan plateau and Himalayas, and the tundra in the Siberian and Canadian North.

It also includes all the states that have renounced nuclear weapons and are part of the Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones, e.g., those established through the Treaties of Tlatelolco (Latin America and the Caribbean), Bangkok (Southeast Asia), Rarotonga (Oceania), Pelindaba (Africa), and Semipalatinsk (Central Asia).

In a real nuclear conflict, targets would almost certainly not be picked at random, but rather focus on military targets or population centers in countries directly at war.

Whatever way you turn it, even after all disarmament efforts, the number of nuclear warheads is still too damn high. We have come a long way, but a lot still remains to be done.

How Do We Lower the Risk?

There are a number of approaches.

Governments can, for example,

- adopt a treaty to become part of a nuclear-weapons free zone,

- remove their nuclear weapons from hair-trigger alerts,

- adopt a no-first use policy,

- sign and ratify the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons to stigmatize these weapons of mass destruction,

- and (re-)start arms control, confidence-building, and non-proliferation measures,

while civil society can

- educate and inform policy makers and the electorate about the dangers of nuclear weapons,

- influence their governments through elected representatives, protests, and petitions,

- and support existing non-governmental organizations aiming to change nuclear policy.

These are all essential steps to reduce the immediate danger from nuclear weapons.

But as Joseph Rotblat, Albert Einstein, and Bertrand Russell noted almost 70 years ago, arms control and disarmament are only fragile, temporary solutions. War must cease to be a legitimate institution to resolve disputes. Military confrontation must be replaced by a peaceful way of settling conflicts.

The Russell-Einstein Manifesto ends with a plea to the United States Congress that has not lost any of its importance and relevance:

In view of the fact that in any future world war nuclear weapons will certainly be employed, and that such weapons threaten the continued existence of mankind, we urge the governments of the world to realize, and to acknowledge publicly, that their purpose cannot be furthered by a world war, and we urge them, consequently, to find peaceful means for the settlement of all matters of dispute between them.

If this sounds too Utopian, the same spirit can be found in Hans Morgenthau’s Politics Among Nations, the bible of political realism.

Men do not fight because they have arms. They have arms because they deem it necessary to fight. […] What makes for war are the conditions in the minds of men which make war appear the lesser of two evils. In those conditions must be sought the disease of which the desire for, and possession of, arms is but a symptom. So long as men seek to dominate each other, to take away each other’s possessions, fear and hate each other, they will try to satisfy their desires and to put their emotions to rest. Where an authority exists strong enough to direct the manifestations of those desires and emotions into nonviolent channels, men will seek only nonviolent instruments for the achievement of their ends. In a society of sovereign nations, however, which by definition constitute the highest authority within the respective national territories, the satisfaction of those desires and the release of those emotions will be sought by all the means which the technology of the moment provides and the prevailing rules of conduct permit. These means may be arrows and swords, guns and bombs, gas and directed missiles, bacteria and atomic weapons.

Morgenthau recognized the crux of all peace efforts in the unrestricted sovereignty of nations and the security dilemma resulting from it. International institutions can only do so much if they are not given the means to enforce the principles they were created to promote and defend. The legal impunity with which Putin is able to command a war of aggression is a touchstone for the shortcomings of global political institutions.

Benjamin Ferencz, chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials and life-long peace activist, expressed it better than anyone:

Yesterday’s legal institutions are hopelessly inadequate for the problems of today and especially tomorrow. We need new ways of thinking and improved mechanisms to guarantee peace and human dignity to everyone. World federalists recognize that survival requires global solutions to global problems. They deserve support by all who value universal human rights and social justice.

A lot needs to be done to reform global institutions to make them more democratic, accountable, and more effective at protecting humanity. But if the 12705 nuclear warheads remind us of anything, then of the fact that it must be done. ⬢

If you found this interesting, consider sharing this article with others.

Methodology

Data on nuclear weapons is taken from the excellent website Status of World Nuclear Forces by the Federation of American Scientists (2022).

The map has been created with QGIS. 12705 points are distributed randomly on an equal-area world map projection using the Random points inside polygons plugin in QGIS. Map data comes from the Natural Earth dataset.

The charts have been created using Adobe Illustrator.

Originally published on Substack on February 22, 2023.